“Too often we give children the answer to remember rather than the problem to solve.”

--Roger Lewin

When I ask our students, “What is your favorite thing about PKS?” more than a few say, “Wonderworks!”

It is easy to see why: students are given time to pursue a passion project; they are given the support they need to feel successful; they have the opportunity to design and iterate based on feedback from peers and from teachers; and they feel the thrill that comes from creating something sui generis.

When I enter classrooms and see students working on their Wonderworks projects, the joy and engagement are self-evident. But Wonderworks is more than this -- it is also a lever to create future scientists, writers, mathematicians, and activists.

I was reminded of this later function as I read an interview with famed scientist EO Wilson. He was reflecting on the damage our obsession with STEM education has had on encouraging children to enter the hard sciences. He believes this obsession has backfired by turning the path towards a STEM career into an endless, tedious rat wheel divorced from developmentally appropriate challenges. He believes that,

“The right way to create a young scientist who’s going to be on fire by the time they’re

in college is to let them pick something, some subject, that has really excited them.

If they dream of space exploration, if they dream of curing a cancer,

if they dream of going to distant jungles and discovering new species —

whatever their dream is, let them dream.”

I love this reminder from Wilson (and I think it applies to more than just STEM careers). I also love working at a school that doesn’t merely pay lip-service to letting kids dream and letting them pursue their passions. We have built dreaming into our routines and we have carved out an entire part of our program that is focused on passion projects.

We have a 3rd grader who dreams of 3D printing a rocket on the moon (following up on the 嫦娥四号, which, earlier this year, became the first craft to land on the dark side of moon); a sixth grader who dreams of opening a food truck to serve 兰州拉面 (parked at the foot of the Twitter building, charging $26/ bowl); a 5th grader who wants to help identify ideal sites in every SF neighborhood for Homeless Navigation Centers.

These are big dreams.

So how do we help students coax them into reality? We start with a focus on mindset rather than skill set: students must engage with their work ready to fail, iterate, fail, iterate, and fail again. In the parlance of our times, we ask them to “fail quickly.”

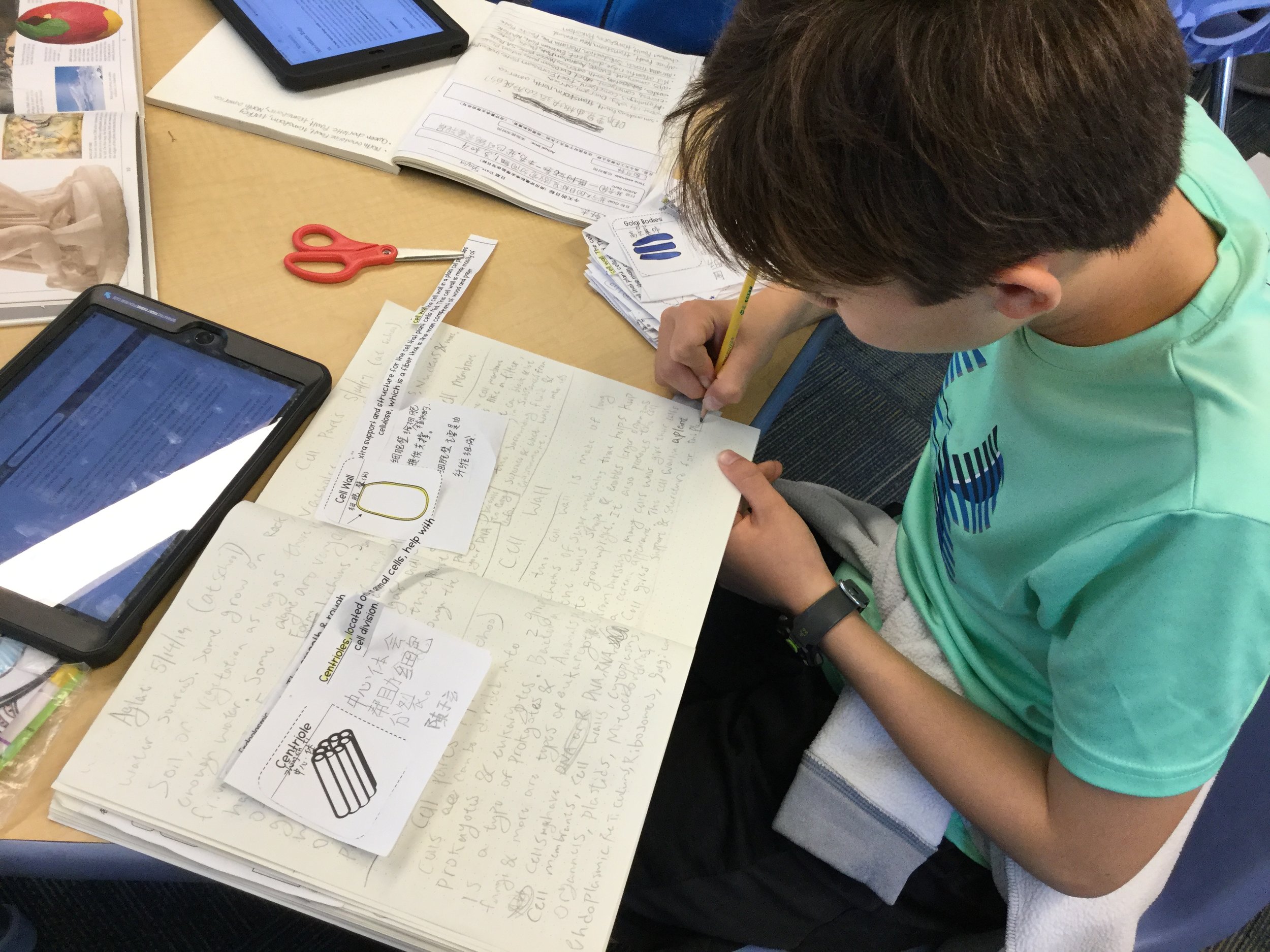

Once a student embraces this mindset, we move on to crucial skills: long-term planning; setting daily goals, tracking those goals, and resetting for the next day; research and organization skills; knowing when, how, and where to ask for help; giving and receiving feedback; knowing when to lead and when to follow; and finally, the writing, public speaking, or design skills needed to finish the project.

At each grade level, this work looks a little different. It is based on what we know in general about the developmental stages of childhood, and what we know in particular about each of our students.

It is also based on research that is both intuitive and easy to forget: passions are not actually “found.” They are developed. We are almost always bad at things the first time we do them, or perhaps the first ten or one-hundred times. Our work is to create a community in which students are willing to grind. The Times offered a nice analogy that reminds how good we are at doing this with infants... and then get worse and worse as our kids get older:

“Think of toddlers learning to walk. They struggle to find strength in their legs and not

trip every few steps, but parents cheer them on instead of focusing on the failures. While

we’re not all lumbering toddlers, the point is that many of us rarely feel that positivity

and encouragement around our endeavors later in life.”

At home, we hope that you will ask your kids, “What was hard today?” Listen carefully to their answers. Don’t feel like you need to coach them or give them advice! It is enough to say, “That does sound hard. I’m really proud of you for sticking with it!” In other words, at home, help reinforce our work on mindset.

For some upper elementary (and all middle) school students, it can also be a nice nightly practice to ask, “What are your goals for tomorrow?” If the goals are vague, (“I will do more research.”), help your kids articulate goals that can be measured. “What will it look like if you’ve succeeded?”

Our students love Wonderworks because they feel successful; because they can operate with increased autonomy; because they are working on projects that have meaning beyond the four walls of their classroom.

I love Wonderworks because it is an opportunity to move away from treating our kids like science, history, or Chinese/ English students and instead treat them like scientists, historians, and writers.